This paper was presented at the Mind-4 conference, Dublin City University, Dublin, Ireland, on August 17, 1999.

[02] In exploring the differences in approaches to subjective experience in our respective fields, it became apparent that cognitive science assumptions and methodologies were based primarily on a positivist paradigm, while Mary's work in family therapy was based on a constructivist paradigm. Seeing the hard problem of consciousness through this lens, it became clear that the positivist paradigm, by virtue of its assumptions that knower and known are separate and uninfluenced by each other, a priori situates the study of subjective experience outside the limits of what can be known. We wondered what the implications might be if cognitive scientists were to step inside an alternative thought system and rework questions like the hard problem of consciousness, starting with a new set of assumptions.

[03] The purpose of this paper is to contextualize the study of subjective experience within the constructivist epistemology, ontology, and methodology. We will view this process through the lens of constructivist therapy/research, providing an example that may be translated to other fields, most particularly that of cognitive science. We begin by contrasting positivist and constructivist paradigms according to Lincoln and Guba's (1985) five differentiating axioms. Secondly, we present evidence of the constructivist paradigm currently emerging across many disciplines (Schwartz & Ogilvy, 1979), but seemingly to a lesser extent in the hybrid field of cognitive science. We present Varela's (1996) fourfold classification of research approaches to the study of the hard problem of consciousness, noting that his phenomenological approach most closely approximates our own.

[04] We then discuss constructivism as it has evolved in the field of psychotherapy. We give particular attention to Lincoln and Guba's (1985) premise that for constructivist inquiry to be meaningful, it is crucial that the paradigm, the model guiding the inquiry, the inquirer, and the methodologies, be congruent. Therefore, the guiding premises of the constructivist model must be embodied or lived, not just thought or spoken about. We explore a number of assumptions regarding the use of a constructivist approach and illustrate such an approach with exemplars drawn from Mary's psychotherapy practice. In her practice, the therapeutic process is synonymous with that of qualitative research, and the therapist/researcher herself is the primary research instrument. We then present new distinctions and categories for describing subjective experience in a holistic manner as subsystems of congruence or flow. These categories may serve as a basis for further research.

[05] We conclude that questions regarding the hard problem of consciousness might be usefully re-examined in light of the constructivist-informed methodology. This alternative view might serve as a means to question the efficacy of the positivist presuppositions that have been guiding much of the consciousness research in cognitive science. We argue that constructivist assumptions and methodologies might open up areas that have been impossible to reach from within the positivist thought system, and we offer some case exemplars drawn from the family therapy field as potential starting points.

[07] Varela (1996) classified proposed solutions to the hard problem of consciousness into four categories. The first, neuro-reductionism (Churchland & Sejnowski, 1992; Crick, 1994) "seeks to solve the hard problem by eliminating the role of experience in favor of some form of neurobiological account which will do the job of generating it" (Varela, 1996, p. 333). The second approach, labeled functionalist (Baars,1988; Calvin, 1990; Dennett, 1991; Edelman, 1989; Jackendoff, 1987), "relies almost entirely on a third-person or externalist approach to obtain data and validate the theory. Its popularity rests on the acceptance of the reality of experience and mental life while keeping the methods and ideas within the known framework of empirical science" (Varela, 1996, p. 333). The third approach, mysterianism (Nagel,1986; McGinn, 1991) concludes that, based on intrinsic limitations of the means through which our knowledge of the mental is acquired, the hard problem is unsolvable.

[08] The final approach, phenomenology, gives an explicit and central role to first-person accounts and to the irreducible nature of experience (Chalmers, 1996; Flanagan, 1992; Globus, 1995; Johnson, 1987; Lakoff, 1999; Searle, 1992; Varela, 1996). Within this approach, a great diversity of proposed methodologies can be found. Phenomenology is Varela's methodology of choice for approaching the hard problem of consciousness, as it is congruent with his view that "any science of cognition and mind, must, sooner or later, come to grips with the basic condition that we have no idea what the mental or the cognitive could possibly be apart from our own experience of it" (Varela, 1996, p. 333).

[09] Our inquiry presented in this paper goes beyond methodological and pragmatic concerns, challenging the positivist world view or paradigm from which the hard problem of consciousness is formulated. Our research is guided by a constructivist [note 2] paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994; Lincoln & Guba, 1985).

With the holographic metaphor come several important attributes. We find that the image in the hologram is created by a dynamic process of interaction and differentiation. We find that the information is distributed throughout -- that at each point information about the whole is contained in the part. In this sense, everything is interconnected like a vast network of interference patterns, having been generated by the same dynamic process and containing the whole in the part (Schwartz & Ogilvy, 1979, pp. 13-14).

We suggest that perspective is a more useful concept. Perspective connotes a view at a distance from a particular focus. Where we look from affects what we see. This means that any one focus of observation gives only a partial result; no single discipline ever gives us a complete picture. A whole picture is an image created morphogenetically from multiple perspectives (Schwartz & Ogilvy, 1979, p. 15).

| Axioms | Positivist Paradigm | Naturalistic Paradigm |

| The nature of reality | Reality is single, tangible, and fragmentable | Realities are multiple, constructed, and holistic. |

| The relationship of knower and known | Knower and known are independent, a dualism. | Knower and known are interactive, inseparable. |

| The possibility of generalization | Time-and context-free generalizations are possible. | Only time- and context-bound working hypotheses are possible. |

| The possibility of causal linkages | There are real causes, temporally precedent to or simultaneous with their effects. | All entities are in a state of mutual simultaneous shaping, so that it is impossible to distinguish causes from effects. |

| The role of values | Inquiry is value-free | Inquiry is value-based |

[12] Axiom 1: The nature of reality (ontology)

[14] Pioneering her own tradition of family therapy, Virginia Satir contributed both a holistic model of congruence and wellness and a clinical methodology congruent with the model. She, like Erickson, emphasized peoples strengths, and like Erickson, used herself as the primary instrument. Both relied primarily on tacit (intuitive) knowledge and informal interview to understand clients' subjective experience in a meaningful way. Thus, the therapeutic processes of Erickson and Satir quite closely paralleled what Lincoln and Guba (1985) describe as the flow of naturalistic inquiry:

The human instrument builds upon his or her tacit knowledge as much as if not more than upon propositional knowledge, and uses methods that are appropriate to humanly implemented inquiry: interviews, observations, document analysis, unobtrusive clues, and the like. Once in the field, the inquiry takes the form of successive iterations of four elements: purposive sampling, inductive analysis of data obtained from the sample, development of grounded theory based on the inductive analysis, and projection of next steps in a constantly emerging design (pp. 187-188).[15] Contrary to the positivist view that "inquiry is value-free and can be guaranteed to be so by virtue of the objective methodology employed" (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 38), we believe that "inquiry is influenced by the choice of the paradigm that guides the investigation into the problem" (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p. 38). For this reason we re-examine the traditional positivist paradigm contrasting it with an alternative thought system that we will refer to as the constructivist paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994).

|

|

Therapies Informed by Positivist Paradigm | Therapies Informed by Constructivist Paradigm |

| The Nature of Reality | One single, true discoverable, knowable and fragmentable reality | Multiple versions of holistic co-constructed, invented realities |

| There is one knowable and true self to be discovered and understood | There may be multiple versions of "self"; "self" is an invented construct | |

| Human experience is fragmented with rational aspects emphasized; emotions are treated as separate from the rest of human experience | Human experience is holistic and holographic; emotional experience is ongoing and simultaneous with the rest of experience; emotions are continuous support factors affecting all human experience | |

| Reality is divided into right or true and wrong or false versions | Many interpretations are possible. No one is any more right or true than any others | |

| The Relationship between the Knower and the Known | Hierarchical, authoritarian, patient and therapist are separate, independent, and dualistic: therapist is "objective" expert | Collaborative; client and therapist both have areas of own expertise; interactive, inseparable, co-creators of experience; mutually influenced |

| Therapist diagnoses problem, unilaterally sets goals, and decides when to stop treatment | Client and therapist collaborate to formulate problem in solvable form and together determine when to stop sessions | |

| The Possibility of Generalization | Absolute time and context free generalizations, such as diagnoses and prognoses are possible | Time and context-bound tentative working hypotheses are possible |

| The Possibility of Cause-Effect Linkages | There are real causes that temporally and sequentially precede their effects | All entities are in a state of mutual simultaneous shaping, so it is impossible to distinguish causes from effects |

| Therapy is generally temporally oriented to the past to attempt to change the future | Therapy is generally temporally oriented to the present and future | |

| Problems are situated within people | Problems are constructed between people | |

| Therapy generally focuses on issues that caused or maintained the problem | Therapy generally focuses on what might be getting in the way of solving the problem/ attaining a desired goal | |

| The Role of Values | Value-free: therapist is assumed to be value-neutral and objective | Value-based: both therapist's values and client's values are assumed to affect treatment outcomes |

| Uses normative-based assessments to evaluate client | Generally does not do formal assessments. Client serves as his/her own norm or chooses norm | |

| Therapist compares client to societal versions of "normal and abnormal" which are assumed to be "right" and "true' | Client and therapist establish what are useful self-self and self-other bases of comparison. Reference points may be multiple and flexible | |

| Therapist helps client move away form pathology | Therapist helps client move toward wholeness and health | |

| Therapist assigns meanings for the client; interprets clients' communications according to therapist's preferred model | Therapist attends to what is important to the client, helps client clarify meanings and assign their own interpretations |

Table 2. Contrasting Positivist and Constructivist therapies (after Lincoln & Guba,1985, p. 37)

[18] In psychotherapy, the term "constructivism" generally refers to an epistemological perspective where people are seen as actively participating in organizing and developing their own lives and meanings. While there are variations of constructivism (see Lyddon, 1995, for a comprehensive review of constructivist perspectives in psychology), they generally seem to sort themselves out in terms of issues regarding whether or not there is an objective reality, and if that reality exists, is it knowable. If the assumption held is that there are only subjective realities, the questions center on whether that experience exists only when it is (co)-constructed or, if it exists only when it is invented. The invented reality position suggests that nothing exists outside of our own inventions.

[19] Modern versions of constructivism have evolved from the philosophical traditions of Vico (1725/1948), Kant (1791/1969), and Vaihinger (1911/1924), as well as the seminal contributions of Piaget's (1926) genetic epistemology, Bartlett's (1932) constructive analysis of human memory, and Kelly's (1955) personal construct theory. Constructivist thinking has emerged as a major perspective in several areas of psychology including cognitive and narrative psychology (Bruner, 1990), psychotherapy (McNamee & Gergen, 1992), social psychology (Gergen, 1982, 1991), and family therapy (Hoffman, 1985; 1990a; 1990b; Keeney, 1983; Watlzlawick, 1984).

[20] Constructivism has been defined by family therapy in three major ways: radical constructivism (von Glasersfeld, 1987), social constructionism (Gergen, 1985; 1991), and constructivism (Varela, 1979). Radical constructivism presupposes that there is an external reality and that a person (or other organism) perceives the world only indirectly through a complex series of neurological transforms. The organism is viewed as being capable of proactivity and the basic unit of perception is individual, rather than social.

[21] In the social constructionist view, the basic way of knowing is also intersubjective or social, rather than neurophysiological. Instead of perception being a function of externally based construct, knowledge is thought to be a moment-by-moment, co-created, communicative artifact. "Social constructionist theory posits an evolving set of meanings that emerge unendingly from the interactions between people. These meanings are not skull-bound and may exist inside what we think of as an individual ‘mind.’ They are part of the flow of constantly changing narratives. Thus, the theory bypasses the fixity of the model of biologically-based cognition, claiming instead that the development of concepts is a fluid process, socially derived" (Hoffman, 1990b, p. 3).

[22] Varela's (1996) constructivist orientation views consciousness

as social and treats the mind and the world as mutually overlapping or

embodied.

Varela (1979) "emphasizes that the observing system for him always means

an observer community, never a single person, since we build our perceptions

of the world not only through our individual nervous systems but through

the linguistic and cultural filters by which we learn" (Hoffman, 1990a).

We share the social constructionist, epistemological view and also the

experiential, intersubjective perspective which includes the body in the

description. Thus, if we were to label our position, it might be called

"social constructivist". For the purposes of this paper, however, we will

continue to reference our view as simply "constructivist."

[24] Many comprehensive examples of honoring clients' frames of reference and theories of change are immanent in the work of Milton Erickson and Virginia Satir. Probably the closest overt reference to this process is Erickson's (1958) notion of "utilization." Utilization refers to the general "process of incorporating aspects of the client's current behavior and perceptions, current and past relationships, life experiences, innate and learned skills and abilities into the therapeutic change process, noticing an individual's uniquely personal responses, resources and skills, and then utilizing them to help clients reach their goals" (Dolan, 1985, pp. 6-7). While Satir did not give a particular name to the process Erickson referred to as utilization, she embodied it. However, unlike Erickson, who never attempted to describe the model characterizing his work, Satir did provide detailed and highly explicit accounts of how she translated her intuitive knowledge of wholeness into the moment-by-moment experience of doing therapy. Other than Satir's writings, most references to the process of how to incorporate the client's worldview and theory of change are vague and illustrated with abstract concepts not directly translatable into action. Thus Satir's writings provide important clues for how to bridge thought with action, and action with thought; inherent in her detailed descriptions of the joining process is her tacit sense of the flow of wholeness.

[26] Constructive therapy, as the first author (Hale-Haniff) has practiced

and taught, is an attempt not only to think about the assumptions and implications

of constructivist methodology, but also to live them. As an example of

an enacted research paradigm, Hale-Haniff has attempted to consciously

and congruently be the research instrument. In doing so, she has

acknowledged the importance of value-congruence across the choice of approach

to inquiry, assumptions of the inquirer, and choice of model as vital to

the experience of meaningful inquiry.

[28] The major differentiating characteristic between positivist and constructivist paradigms is the notion of wholeness. Satir translates the awareness of wholeness, which is largely a fixed, spatial metaphor, into temporal form, expressed through the infinite continuity or flowing movement of attention. Her concept of congruence refers to holistic patterns of consciousness in which attention flows freely and continuously (Satir, 1967; Satir, 1988; Satir & Baldwin, 1983; Satir, Banmen, Gerber, & Gomori, 1991). When all bits of information in consciousness are congruent with each other, there is flow, and the quality of experience is optimal; when they conflict, the attention pattern becomes blocked or repetitive, and experience is painful. Satir attended to congruence or lack of congruence at multiple simultaneous levels: values, intention, attention, and behavior.

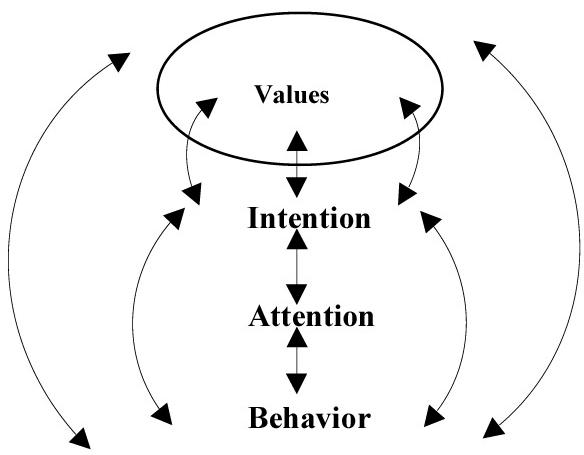

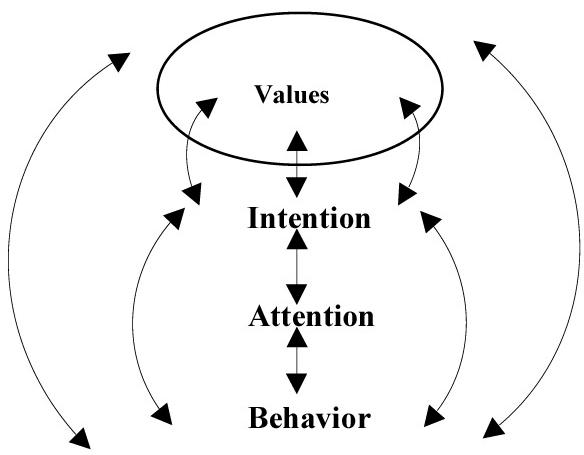

[29] Satir (1967), attempting to cut through the barriers of disciplines and models, examined basic processes that occur in all human relationships. She believed that "the future of human relations disciplines and modalities lies in the integration of their various partial views of man in relation to the four basic parts of self, which are: a.the mind, b.the body, c.the report of the senses (the interaction between the mind and body), and d.interaction with others (social relationships)" (pp. 178-179). Thus, the aim of therapy was integration of the whole person, achievable by the process of becoming more congruent with self and others. For over twenty-five years, Csikszentimihaly (1978; 1990; 1997) studied optimal experience, or flow states, in hundreds of individuals from around the world, as they engaged in many different activities. We see an isomorphic relationship between the pattern and structure of Csikszentmihaly's flow states and Satir's description of congruence. Both reference the inter-relationships among the subsystems of values, goal setting or intention, attention, emotion, and behavior. Diagram I summarizes the relationships among these subsystems of subjective experience.

[30] Csikszentmihaly's phenomenological approach (1978; 1990; 1997), which is based on information theory, provides clear and useful descriptions of the relationship between values, intention, attention, and emotion. Values are the major arbiters of choice.What we value, that which is important to us, is pervasively reflected across all aspects of consciousness: in our implicit and explicit choices, philosophical orientation and rules to live by, the nature of our expectations and assumptions, decision-making, means of motivation, prioritization of goals, choices in what we attend to, how we behave. Intention or goal-setting is the force which keeps experience ordered. Goals or intentions, which may be immediate, short, or long range, are assigned many levels of priority, ranging from trivial to vital. Attention refers to what will and will not appear in consciousness--what we notice internally and externally. At any given moment, we have at our disposition many individual units of attention which may be usefully categorized as auditory, visual and kinesthetic in nature. Behavior is what we say, how we say it, and body language (Satir, 1967).Diagram I: Relationships among the Subsystems of Congruent Subjective Experience (Hale-Haniff, 1989)

[31] An unconflicted or unified intent presupposes clearly prioritized values supported by compatible or unconflicted assumptions, and in patterns of attention where people are predisposed to notice that which is congruent with goals. This alignment of values, intention, and attention, supports those emotions and behaviors that are congruent with the objective. On the other hand, conflicted or split intentions presuppose unprioritized values and/or conflicting beliefs which result in patterns of attention that include both relevant and irrelevant stimuli, and are accompanied by mixed emotions, and inconsistent or dissonant behaviors.

[32] There is also a relationship among intention, attention, and emotional experience. Negative states are those in which disorganization of the self impairs its effectiveness. The opposite condition, flow, is experienced "when information coming into consciousness is congruent with goals, and psychic energy flows effortlessly" (Csikszentmihaly, 1990, p. 39). According to Csikszentmihaly (1997), negative emotions, like boredom, anxiety or fear, produce a state from which people are not able to use attention to effectively deal with external tasks. Instead, they must turn their attention inside to restore order. Conversely, when people experience states of positive emotion, like confidence, joy, or strength, attention is no longer fixated internally, and thus can flow freely both internally and externally. "Flow helps to integrate the self because in that state of deep concentration consciousness is unusually well ordered. Thoughts, intentions, feelings, and all the senses are focused on the same goal" (Csikszentmihaly, 1990, p. 41).

[33] All subjective experience is not value-driven; news of a difference (Bateson, 1972) can enter the system from any point and move in any direction. However, psychotherapy as we practice it, is a value and intent driven phenomenon. Just as we have implemented well-formedness conditions (de Shazer, 1991) as guides for setting outcomes, we have integrated Satir's principles of congruence as a well-formedness template for integration of human systems. When all subsystems of a person are aligned or congruent, he or she experiences a centered state or flow state. Satir's model can serve both longitudinally as a model for personal growth, and situationally as a guide for adjustment of intra and inter-personal communications.

[34] We have already conceptualized congruence at a larger level in

the descriptions of relationships among the values, intentions,

attention, and behavioral subsystems, and will now turn our attention to

ways in which varying degrees of congruence may be reflected within

the subsystems. Descriptions will highlight visual and kinesthetic ways

of knowing and communicating that are perceptible in lived experience on

a moment-by-moment basis.

A value is simply a criterion or touch stone or perspective that one brings into play implicitly or explicitly in making choices or designing preferences. In this sense values would encompass all of the following: assumptions or axioms, theories or hypotheses, perspectives, social-cultural norms, personal-individual norms.[36] Values refers to the sense that something is or is not important. Beliefs are assumptions, convictions, rules or expectations about life, people and ideas. We tend to hold beliefs only about things that matter to us, that is we formulate beliefs around what we value. This section will first address congruence within values and beliefs as separate systems, and lastly as integrated systems.

[38] These criteria are so consistently referenced that we develop deep, strong responses when accessing them. A person can express what is important to them in any and all sense systems. Visually, most important items tend to be at the top of a list and descend on a scale to least important. What is important is larger in size and more clearly focused, while that which is not is smaller and less in focus. What is of importance tends to be relegated a central position, and what is not, a peripheral one. Gesturally, people tend to use upward hand gestures to indicate what is more important and downward gestures for what is less important, wide arm gestures for what is most significant and small hand and finger gestures for what is trivial. Gestures tend to be emphatic and precise when referring to highly held criteria, and looser and more random for what doesn't matter much.

[39] Verbally, we use language patterns that often parallel visual and gestural communications. For example, we speak of high and low priorities, of issues being of central or peripheral importance, of large and small issues, of making mountains out of molehills, and of focusing or bringing into view what is really important so we don't get lost in the details. We also speak of deeply held values and core values. Linguistically, we often use changes in tonality, loudness, and rhythm to stress what matters most to us. In addition, importance is sometimes indicated by repetition of certain themes, words, or content.

[40] Kinesthetically, what is important is indicated by using the hands to weigh two sides of an issue, with the most important tending to have more weight. On the torso, value-based kinesthetics tend to be central or midline and to be very deep body sensations. These are often indicated gesturally with two hands, palms facing the body and fingers pointing to where the kinesthetic sensation is located. Generally, there is always a change from baseline affect as indicated by what is said, how it is said, and body language when a person is communicating something that is important to them. Values tend to be highly enduring over time and reflect an integration of thinking and feeling processes.

[41] Congruence in value systems is correlated with people sorting out what they do value from what they think they should value as well as sorting what they do want from what they don't want. The former involves separating social mores from personal ones, or at least making conscious decisions of what we as responsible adults wish to embrace. This supports looking at old values to reevaluate and update these past learnings based on whether they are congruent for us at this time (Satir et al., 1991).

[42] It is also important that what people want (or positive values) be clearly sorted out from what they don't want (or negative values). This is important because deep kinesthetics are associated with both positive and negative criteria, and feeling drawn to and repulsed from at the same time leads to emotional conflict with excess attention in the emotional arena, and less attention on criteria for deciding what action might be useful to take. In goal setting, people must be able to access positive values to chart a direction for themselves and establish feedback loops that allow them to adjust their behavior in order to achieve the desired outcome. For example, a person whose goal is not to smoke is stating a negative value. This will provide movement or motivation, but not direction or feedback. So adding positive criteria like, "I want to be able to run up both flights of stairs without puffing" and "I want my home and fingers to smell clean," reference positive criteria and provide a course of positive action and feedback indicating that the goal is being approximated.

[43] Besides sorting positive from negative values, it is important that values are prioritized from most to least important. This leads to more consistent motivation, decision-making, and planning, and also brings forth patterns of attention and emotions which support intentions. Split or conflicted intentions can result from values that are not clearly prioritized, but also can be a function of conflicting beliefs or assumptions.

[45] Another way to discern beliefs is by our emotional responses. Emotional responses provide cues that one or more of our (conscious or unconscious) expectations are being violated. For example, when someone else has violated an important belief or expectation, feelings of disappointment, anger, or hurt often ensue. Because these emotions serve as signals of unmet expectations, they can serve as catalysts for identifying unconscious expectations or beliefs. In this manner, a person can be in a position to either reformulate his expectation to be more "realistic," or adjust other aspects of the relationship. If the expectation happens to reflect a very deep value, the person may choose to re-evaluate the nature of relationship rather than to be incongruent with himself.

[46] When we set expectations for ourselves and do not honor them, we typically experience an emotion like "guilt" Conversely, when other people do not meet an important expectation or violate an important value, "anger" is often the emotion experienced. The significance of this discussion is that reoccurring emotional responses may be harnessed as useful tools for helping people identify and shift key beliefs or expectations. In addition, when feelings are accessed with reference to key expectations and values, the balance of attention between emotional experience and thinking maintains flow states of attention.

[47] In contrast to values which are typically communicated gesturally by referencing a vertical continuum, ranging from what is most to least important, beliefs range on a side-to-side continuum ranging in relative degrees of doubt or conviction. An important determining factor in the perceived strength of a belief is the presence or absence of coexisting conflicting beliefs. Firm convictions are by definition, unconflicted; weak; "wishy-washy" ones generally either presuppose the presence of conflict, or a very low level of importance. For example, an individual may believe that she deserves the day off, but also believe she should go to work because of responsibility to coworkers. She may eliminate the conflict by identifying the values attached to both of the beliefs (valuing mental health versus taking responsibility). Then she decides which value is of highest priority given the bigger picture of her mental health, general pattern or responsibility plus her guiding vision and mission. If part of her vision and mission is to live life based on principle, those principles will temper the shorter-term situational emotions or preferences that otherwise may have led her to make a less congruent decision.

[49] The integration of value and belief systems into a congruent whole is not without its challenges. One reason for this is because people learn and generalize (and sometime over-generalize) as fast as they do. For example, if a young child touches a hot stove and generalizes that experience to "never touch a hot stove again," we might call that a useful generalization. However, if that same child is burned in a relationship and generalizes never to trust again, we call that an unuseful belief or over-generalization.

[50] Another reason integration has been somewhat difficult is that we have all received mixed input over the course of our growing up. Different teachers, relatives, parents, television and movie heroes and heroines have all have provided us many varying messages across time, which have led to many conflicting beliefs and expectations. The variation of degree and type of value systems has increased in the information age we live in and perhaps much conflict is a function of the "cross-pollination" of our belief and values systems. This has been occurring in this country and many other parts of the world as well. While people used to grow up in the same town surrounded by the same families who embraced similar belief and value systems, we now have families relocating (and relocating) on a frequent basis. With the dawn of the information age, we have access to input to many different cultures. Globally, many professions are challenging what were bedrock beliefs in Western culture's predominant ways of thinking and being.

[51] All this is providing input to challenge our existing belief and

value systems. The key word here is systems. Beliefs and values

operate systemically, and are held together by certain cornerstone beliefs

and foundational principles. When people receive mixed input regarding

what were previously considered to be "unshakable" beliefs, the entire

system begins to lose its sense of stability. It is during this time flux

that revisiting and reclarifying key beliefs and values is becoming essential.

[53] The co-creation of a shared intention or situational goal defines

client and therapist - in a very literal sense - as an inseparable unit.

It is the joint intention that manifests the axiom that knower and known

are inseparable; client and therapist moving together as one mind toward

a shared goal. When joined in intention, there can be no perception of

resistance or lack of cooperation (de Shazer, 1984; 1985; 1991), since

the very notion of resistance presupposes separate goals and intentions

where one "resists" the other. Particularly important, the process of establishing

clear, joint intentions automatically predisposes therapist and client

to notice stimuli useful to the achievement of their goal. Therefore, setting

joint intentions functions as a frame which operates much like any model:

it helps to accentuate certain aspects of communication and not others

(Bateson, 1972).

[55] Rapport is an ongoing, mutual-shaping phenomenon: In the

positivist view, rapport is generally described as a set of instrumental

activities a therapist does at the beginning of a session to "gain" cooperation

and access to information (Jorgenson, 1995). In a constructivist view,

however, rapport is an ongoing, moment-by-moment process, developing and

maintaining communicative fit with the client system. This process of developing

fit is characterized by the therapist adjusting him or herself to enhance

fit with the client system. Conceptually, the goal is to continually accommodate

oneself to the client's world view and theory of change (Duncan et al.,

1997), thus maintaining a communicative fit between client and therapist.

This process is shaped by the joint intention of therapist and client;

each is predisposed to notice and approximate aspects of each other's behavior

in line with that intention.

[58] Attending to the sense system presupposed in clients' language

is based on the assumptions that sensory experience or "the report of the

senses" reflects the interaction between body and mind, and that one can

attend to communication behavior as a simultaneous manifestation of sensory

experience (Satir, 1967). By carefully attending to communication behavior

in an ordered manner, Satir was able to help clients co-construct new emotional

experiences. These behavioral cues fit into the general categories of what

you say, how you say it, and body language (Satir, 1967). Table 4

summarizes examples of communication behaviors by the sensory modality

they presuppose.

| Visual | Auditory | Kinesthetic | ||

| What you say | visual predicates | auditory predicates | kinesthetic predicates | |

| How you say it | higher pitch; less variety of inflection; quality may be nasal or strained; higher rate of speech | mid-range pitch; varied & melodic inflection; moderate, rhythmic rate | lower pitch; longerpauses, breathy slower rate or higher pitch; few pauses, shrill, faster rate | |

| Body Language | Breathing | Breathing high in chest, shallow, and more rapid | Breathing mid-chest; and moderate rate | Breathing low in abdomen, slower rate or holding breath or whole body heaving with breath; & exaggerated rate |

| Eyes | May squint or defocus; eyes may converge to a given point in space, upward eye movements | Side to side eye movements | May lower eyes | |

| Arm, hands, & fingers | Gestures toward eyes; upward movements of arms; may gesture to particular spatial locations | Gestures around ears and mouth; may cross arms; snap fingers; place hand on chin (telephone position) | Gestures toward lower abdomen, mid-line of torso or heart; hand gestures with palm facing body; fingers may move in sync with rhythm of body sensations; Arm and hand gestures may trace sequences of body sensations. | |

[60] In constructive therapy our goal is to utilize co-creations of

subjective experience to help people change. Paying attention to these

process-based distinctions requires detailed attention to "differences

which make a difference" for co-constructing new experience. Like any distinction,

submodalities become more evident by comparison. To illustrate this, if

a client presents with a desire to feel more confident and less fearful

in public speaking, the present state would be "fear" and the desired state

"confidence." The therapist would note differences between the client's

distribution of attention in modality and submodality experience across

the two different states: fear and confidence. The fear state might be

characterized by a general internal orientation of attention to negative

self talk, uncomfortable kinesthetics like high shallow breathing, a weak

feeling in the limbs and butterflies in the stomach, with almost no conscious

visual experience. On the other hand, the confident state might be characterized

by an external orientation of attention, visually focused on the entire

audience, auditorally focus on the way the speaker's own voice and phrasing

is modulating as a function of audience response, and a feeling of relaxed

awareness coupled with a sensation of being ten feet tall. Thus, the therapist's

attention to categories of experience help client and therapist co-create

order and pattern from chaos. In addition, the accompanying physiological

and behavioral cues provide further feedback to client and therapist guiding

communication shifts away from the problem state and toward the solution

state.

| Sensory Input: | Processing : | Behavioral Output: |

| What you notice: the direction & flow of attention. | How you interpret and assign meaning to communication | What you say, how you say it, and body language |

Ability to:

|

Ability to:

|

Ability to:

|

[63] We acknowledge that acquiring the skills we are describing

in this paper is a distinctly different process from actually using

them. Learning each skill involves conscious repetition of listening,

observing, and performing the skill to a point that it becomes a fixed,

and unconsciously automated pattern (Hale-Haniff, 1989). Later, when the

therapist is actually doing therapy, skills are accessed "naturally"

as a function of unconscious pattern recognition. This type of learning

has previously been described by M. C. Bateson (1972).

[65] It is the positivist view which tends to fragment human experience and emphasize the rational aspects. Thus, emotions have generally been conceptualized as separate and apart from the rest of human subjective experience. Most of us have been socialized largely according to positivist thinking, conceptualizing emotions as sudden and intense experiences that come and go at certain times; something that a sane or balanced person learns to keep under control so that rational thinking and control can prevail. On the other hand, the holistic, constructivist view depicts emotional experience as ongoing, simultaneous with and supportive of, the rest of experience. Here emotional experience may be understood as another way of knowing - one that is significantly different from more conscious and deliberate ways of knowing.

[66] Kinesthetic experience occurs holistically in concert with other mind-body experience; it is ever-present (although not always consciously accessible) in form of "feelings of emotion" (emotions being changes in body states), or in form of "background feelings," which correspond to our "body states prevailing between emotions." The latter contribute to our moods, to our proprioception, introception (visceral sense) - in general to our "sense of being" (Damasio, 1994, p. 150). It is important to note that experience that is kinesthetic to the person being referenced (in this case, the client) is accessible primarily visually to the facilitator (the therapist). For example, as I feel my face get hot, you might notice me blush. Or, as I feel a sense of pride welling up in me, you might notice me taking a deep breath as I square my shoulders. Thus learning to detect new categories of sensory experience in oneself and others involves enhancing perception of new categories of both kinesthetic and visual experience. Becoming more consciously aware of categories of sensory experience other than auditory-verbal, the therapist enhances her ability to accommodate to clients.

[67] The therapist uses this information in various ways, depending on the outcome of the session. However, regardless of outcome, information calibrated is always fed back to the client to test for accuracy and recognition. If the therapist's hypothesis is not accepted by the client, it is revised and communication is recalibrated. Information is always compared to something to contextualize and give it meaning. For example, changes in posture, physiology, or affect are detected by first having calibrated the client’s overall attitude or stance during that session. Modality and submodality experience of the problem states is only useful when compared to that of the resource state. When people present in unresourceful or stuck states, they are temporarily unable to perceive a difference that makes a difference that would allow them to regain free flow of information. Well-being is a function of free or varying information flow within and between people.

[69] Although cognitive science is a hybrid discipline that comprises many different fields and even though research emanating from many of these fields is becoming progressively more grounded in the naturalistic paradigm, we don’t see cognitive science overtly and explicitly embracing it. Many cognitive scientists have been calling for new methods to study subjective experience; however, we frequently find ourselves situated epistemologically somewhere on a continuum between positivist and naturalistic paradigms. One difficulty is that the positivist paradigm is highly eminent in "everyday" thinking. Although we are committed to a new paradigm, it still remains a daunting task to leave behind a way of thinking and living that is ingrained in our culture, and socio-political environments: "If it is difficult for a fish to understand water because it has spent all of its life in it, so is it difficult for scientists to understand what their basic axioms or assumptions might be and what impact those axioms and assumptions have upon everyday thinking and lifestyle" (Lincoln & Guba, 1985, p.19-20).

[70] Following are some examples of approaches to the hard problem of consciousness, reflecting varying positions along the positivist-constructivist continuum:

[72] There are those who question how the constructivist-informed inquiry relates to the traditional concept of science and scientific method. To them we respond by quoting Varela:

This is not a betrayal of science: it is a necessary extension and complement. Science and experience constrain and modify each other as in a dance. This is where the potential for transformation lies. It is also the key for the difficulties this position has found within the scientific community. It requires us to leave behind a certain image of how science is done, and to question a style of training in science which is part of the very fabric of our cultural identity (1996, p. 347).

[74] We illustrated the constructivist research methodologies by way of our work in constructive psychotherapy. Constructive therapy was used as an example, as the first author (Mary Hale-Haniff) practiced it, of an attempt to take the presuppositions and assumptions of the constructivist research methods and live them. It is an example of an enacted research paradigm with the researcher attempting to be consciously and congruently the research instrument. Our descriptions encompassed 1) contrasting psychotherapies informed by positivist and constructivist paradigms, 2) an explicit model of wholeness expressed by congruence as flow 3) deconstruction of subjective experience into subsystems of congruence, 4) deconstruction of congruence into subsystems of values, intention, attention, and behavior, and 5) categorization of subjective experience into sensory, process-based, rather than content-based distinctions.

[75] The significance of our work is both practical and conceptual. Both therapist and clients have reported an amplified awareness of their experience as ordered, patterned processes. As a result they have been more able to access positive flow states when needed, and to experience more choice, with respect to unpleasant, chaotic, or unuseful experiences. Besides cross-contexualizing resources within people to help them move away from pain and more toward optimal experience, sensory-based distinctions can be implemented to assist transferring excellent skills and resources between people.

[76] Our work has implications far beyond clinical psychotherapy. It has demonstrated how the paradigm that a researcher embraces shapes her value system--not only in her work, but also in her life. Value subsystems also shape our intentions, use of attention, and behavior in any given context. In this way, our work becomes one with our lives and our philosophy becomes a lived philosophy. Because the constructive research paradigm is a lived paradigm, people who wish to embrace it need to engage in special teaching-training procedures to help them internalize the distinctions such as those which were presented in this paper. Becoming a more exquisite research instrument requires integrating the categories in our bodies--not only in our heads.

2. What Lincoln refers to as the naturalistic paradigm (Lincoln & Guba,1985), she later (Denzin & Lincoln, 1994) refers to as constructitvist. Therefore, we use the terms interchangeably in the text. [Return 2]

3. As this monograph was privately published and may be accessed only at significant expense, we have relied on Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) quotations of Schwarz and Ogilvy’s (1979) paper rather than the original. [Return 3]

Bandler, R., & MacDonald, W. (1988). An insider's guide to sub-modalities. Cupertino: Meta Publications.

Bartlett, F. C. (1932). Remembering. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. North Vale, NJ: Jason Aaronson.

Bateson, M. C. (1972). Learning: An entry into pattern. In Our own metaphor. (pp. 104-120). New York: Knopf.

Bateson, G. (1979). Mind and nature: A necessary unity. New York: Dutton.

Boscolo, L., Cecchin, G., Hoffman, L., & Penn, P. (1987). Milan systemic family therapy: Conversations in theory and practice. New York: Basic Books.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Calvin W. (1990). Cerebral symphony: Seashore reflections on the structure of consciousness. New York: Bantam Books.

Chalmers, D. J. (1995). Facing up to the problem of consciousness. Journal of Cosnciousness Studies, 2 (3), 200-219.

Chalmers, D. J. (1996). The conscious mind: In search of a fundamental theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chalmers, D. J. (1997). Moving forward on the problem of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2 (3), 200-19.

Churchland, P.S., & Sejnowski, T. (1992). The computational brain. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Crick, F. (1994). The astonishing hypothesis.New York: Scribners.

Csikszentmihaly, M. (1978). Attention and the holistic approach to behavior. In K. S. Pope and J. L. Singer (Eds.), The stream of consciousness (pp. 335-358). New York: Plenum.

Csikszentmihaly, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper and Row.

Csikszentmihaly, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

de Shazer, S. (1984). The death of resistance. Family Process, 23, 11-17.

de Shazer, S. (1985). Keys to solutions in brief therapy. New York: Norton.

de Shazer, S. (1991). Putting difference to work. New York: Norton.

Damasio, Antonio R. (1994). Descartes’ Error. Grosset/Putnam.

Dennett, D. C. (1991). Consciousness explained. Boston: Little Brown.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (Eds.), (1994). Handbook of qualitative research. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Dolan, Y. M. (1985). A path with heart: Ericksonian utilization with resistant and chronic clients. New York: Brunner Mazel.

Duncan, B. L., Hubble, M. A., & Miller, S. D. (1997). Psychotherapy with "impossible" cases. The efficient treatment of therapy veterans. New York: Norton.

Edelman, G. (1989). The remembered present: A biological theory of consciousness. New York: Basic Books.

Erickson, M.H. (1954). Pseudo-orientation in time as a hypnotic procedure. Journal of Experimental and Clinical Hypnosis, 2, 261-283.

Erickson, M.H. (1958). Naturalistic techniques of hypnosis: Utilization techniques. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 8, 57-65.

Erickson, M. H. (1965). The use of symptoms as an integral part of therapy. American Journal of Clinical Hypnosis, 1, 3-8.

Fisch, R., Weakland, J.H., & Segal, L. (1982). The tactics of change: Doing therapy briefly. San Francisco, Jossey-Bass.

Flanagan, O. (1992). Consciousness reconsidered. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gergen, K. J. (1982). Toward transformation in social knowledge. New York: Springer-Verlag.

Gergen, K. J. (1985). The social constructionist movement in modern psychology. American Psychologist, 40, 266-275.

Gergen, K. J. (1991). The saturated self. New York: Basic Books.

Globus, G. (1995). The post-modern brain. New York: Benjamin.

Hale-Haniff, M. (1986). Accessing the right brain. Unpublished manuscript.

Hale-Haniff, M. (1989). Changeworker's guide to inter and intra-personal communication. Unpublished manuscript.

Haley, J. (1976). Problem solving therapy. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hoffman, L. (1985). Beyond power and control: Toward a "second-order" family systems therapy. Family Systems Medicine, 3, 381-396.

Hoffman, L. (1990a). A constructivist position for family therapy. In B. P. Keeney, B. F. Nolan, & W. L. Madsen (Eds.), The Systemic Therapist,1 (23-31). St. Paul, MN.

Hoffman, L. (1990b). Constructing realities: An art of lenses. Family Process, 29, 1-12.

Hoffman, L. (1998). Setting aside the model in family therapy. In M. F. Hoyt (Ed.), Constructive therapies: Innovative approaches from leading practitioners. San Franscisco: Jossey-Bass.

Hut, P., & Shepard, R. (1996). Turning the hard problem upside down and sideways. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3 (4), 313-329.

Jackendoff, R. (1987). Consciousness and the computational mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jorgenson, J. (1995). Re-relationalizing rapport in interpersonal settings. In W. Leeds-Hurwitz (Ed.), Social approaches to communication. New York: Guilford.

Kant. I. (1969). Critique of pure reason. New York: St. Martin's. (Original work published 1791).

Keeney, B. P. (1983). Aesthetics of change. New York: Guildford.

Kelly, G. A. (1955). The psychology of personal constructs. New York: Norton.

Lakoff, G. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge to Western thought. New York: Basic Books.

Lambert, M. J. (1992). Implications of outcome research for psychotherapy integration. In J. C. Norcross & M. R. Goldfried, (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy integration, p. 94-129.

Lankton, S. R., & Lankton, C. H. (1983). The answer within: A clinical framework of Ericksonian therapy. New York: Brunner Mazel.

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985), Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Lowe, E. J. (1995). There are no easy problems of consciousness. Journal of Consciousness Studies,2(3), 266-271.

Lyddon, W. J. (1995). Forms and facets of constructivism. In R. A. Neimeyer & M. J. Mahoney, (Eds.), Constructivism in psychotherapy. American Psychological Association: Washington, D. C., pp. 69-92.

McGinn, C. (1991). The problem of consciousness. Oxford: Blackwell.

McNamee, S., & Gergen, K. J. (1992). Therapy as social construction. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Miller, S. D., Duncan, B. L., & Hubble, M. A. (1997). Escape from Babel: Toward a unifying language for psychotherapy practice. New York: Norton.

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. New York: Oxford University Press.

O'Hanlon, W. H., & Weiner-Davis, M. (1989). In search of solutions: A new direction in psychotherapy. New York: Guilford.

Orlinsky, D., Grawe, K., & Parks, B. (1994). Process and outcome in psychotherapy. In A. E. Bergin & S. E. Garfield (Eds.), Handbook of psychotherapy and behavioral change (3rd ed., pp. 270-375). New York: Wiley.

Pasztor, A. (1998). Subjective experience divided and conquered. Communication and Cognition, 31(1), 73-102.

Piaget, J. (1926). The language and thought of the child. London: Kegan, Paul, French & Trubner (original work published 1923).

Satir, V. (1967). Conjoint family therapy (revised ed.).Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books.

Satir, V. (1988). The new peoplemaking. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books.

Satir, V., & Baldwin, M. (1983). Satir step by step: A guide to creating change in families. Science and Behavior Books: Palo Alto.

Satir, V., Banman, J., Gerber, J., & Gomori, M. (1991). The Satir model. Palo Alto: Science and Behavior Books.

Schwartz, P., & Ogilvy, J. (1979). The emergent paradigm: Changing patterns of thought and belief (SRI International). Cited in Lincoln, Y.S., & Guba, E. G. (1985), Naturalistic inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Shear, J. (1996). The hard problem: Closing the empirical gap. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3 (1), 54-68.

Searle, J (1992). The rediscovery of the mind. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Vaihinger, J. (1924). The philosophy of "as if." New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. (Original work published 1911).

Varela, F. (1979). Principles of biological autonomy. New York: North-Holland.

Varela, F. (1996). "The specious present": A neurophenomenology of nowness. In J. Petitot , J. M. Roy, B. Pachoud, & F. Varela (Eds.), Contemporary issues in phenomenology and cognitive science. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Varela, F. (1996). Neurophenomenology: A methodological remedy for the hard problem. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 3(4), 330-349.

Varela, F., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The embodied mind: Cognitive science and human experience. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Velmans, M. (1995). The relation of consciousness to the material world. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 2 (3), 255-265.

Vico, G. (1948). The new science (T. G. Bergin & M. H. Fisch, Trans.). Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press (original work published 1725).

von Foerster, H. (1984). On constructing a reality. In P. Watzlawick (Ed.), The invented reality (pp. 41-62). New York: Norton.

von Glasersfeld, E. (1979). Radical constructivism and Piaget's theory of knowledge. In F. B. Murray (Ed.), The impact of Piagetian theory on education, philosophy, psychiatry, and psychology (pp. 109-122). Baltimore: University Park Press.

Watzlawick, P. (1984). The invented reality. New York: Norton.

Click here to return to the Table of Contents for Dialogues in Psychology.

Click here to return to the Dialogues in Psychology Editorial Statement.